Under current plans, the total number of deployed Ground-based Interceptors (GBIs) of the U.S. Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system will reach a total of 44 by the end of 2017. Three different types (and likely several sub-types) of Exo-Atmospheric Kill Vehicles (EKVs) will be deployed on these GBIs. These are the original Capability Enhancement-1 (CE-I) version, deployed between 2004 and 2007, the follow-on CE-II version deployed between 2008 and 2015, and the new CE-II Block 1, which will be deployed starting in 2017. The differences between these types of EKVs are described in my post of April 26, 2015.

In this post I try to estimate the composition of the deployed GBI force when the 44th GBI is deployed in 2017.

It seems clear that ten of the deployed GBIs will be the new CE-II Block 1 version. This assumes that the first flight and intercept test of a CE-II Block 1, currently scheduled for the third quarter of calendar year 2016, is successful. The MDA currently plans to deliver eleven CE-II Block 1s by the end of 2017, one of which will be expended in the intercept test — FTG-15.

According to the Department of Defense’s Inspector General, through 2015, the U.S. has bought a total of 33 CE-I and 24 CE-II EKVs, for a total of 57.[1] This numbers appears to be the final totals for each of these EKV versions, because by 2016 production will have switched over to the CE-II Block 1. Under current test plans, by the end of 2017, seven CE-Is and six CE-IIs EKVs will have been expended in test flights.[2] These tests will reduce the number of remaining EKVs to at most 27 CE-I and 18 CE-IIs.

According to the 2015 prepared statement of MDA Director Admiral Syring for Congressional committees, “Four previously fielded CE-II GBIs will be used for flight and Stockpile Reliability testing.” Removing these four GBIs leaves 16 deployable CE-II GBIs, since two of the CE-IIs (CTV-02+ and FTG-11) to be withdrawn for testing were already subtracted out of our count in the previous paragraph.

A total of 16 deployed CE-IIs is consistent with Admiral Syring’s statement in his 2015 prepared testimony that eight new CE-IIs would be deployed in 2015 and that eight currently fielded CE-IIs would be upgraded in FY 2016.

With sixteen CE-IIs deployed, the breakdown at the end of 2017 would be:

10 CE-II Block-1s

16 CE-IIs

18 CE-Is

Thus at that point less than half of the deployed GBIs would be CE-Is.

An alternate method of attempting to count the number of deployed CE-II GBIs is included at the end of this post.

Continuing out past 2017:

The further out one goes in time, the more speculative attempts to estimate the EKV stockpile become. However, several general points can be made:

(1) MDA budgetary materials suggest that few if any new GBIs will be deployed using funding from its RDT&E account from 2017 to 2020.[3] All the currently deployed GBIs as well as those planned for deployment through 2017 have been bought through the MDA’s RDT&E account. GBIs usually require several years from initial procurement to deployment, and there are no indications in the RDT&E budget materials of plans to procure additional GBIs for deployment in the near future.

Specifically, in the Ground Based Interceptor Manufacturing budget element for FY 2016, MDA cites only three projects:

— Completing the planned deliveries of CE-II equipped GBIs.

— Continuing the manufacturing of the eleven CE-II Block 1 GBIs planned for deployment (and use in a test) by the end of 2017.

— Beginning acquisition of two new GBI boosters. These are likely the two boosters that will be used in the flight and intercept tests of the new Redesigned Kill Vehicle (RKV) planned for FY 2018 and FY 2019.

(2) Beginning in FY 2018, MDA will begin procuring two GBIs per year under its Procurement account. These GBIs are needed to provide additional GBIs to support flight testing, stockpile reliability, and spares requirements associated with the increase from 30 to 44 deployed GBIs. Under previously announced plans, a total of ten GBIs will be bought over five years for these purposes. Initially, these GBIs will likely be equipped with CE-II Block 1 EKVs and be deployed to free up older deployed GBIs for testing. Thus by about 2019-2020, the numbers of deployed CE-1s will likely to begin declining in favor of CE-II Block 1s. It is possible that starting in 2020, these GBIs will start to be equipped with RKVs — if not, then it seems that both CE-II Block 1 EKVs and RKVs would have to be in production at the same time.

(3) Under current plans, MDA plans to begin deploying RKV-equipped GBIs in 2020. There has been no public indication of how rapidly such new GBIs might be deployed. One possible factor might be that the EKV-equipped GBIs are said to have a twenty-year lifetime, and the last CE-I equipped-GBIs were deployed in 2007. Replacing all of the deployed CE-Is by 2027 would only require an RKV deployment rate of somewhat over two per year. Of course, if it was decided to establish an East Coast interceptor site, the rate of RVK production would have to increase very significantly.

An alternate attempt estimate of the number of CE-II GBIs at the end of 2017:

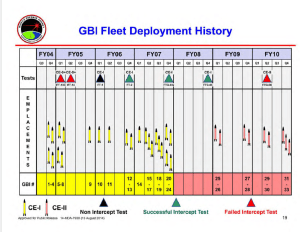

Another way to try to estimate the number of deployed CE-IIs is by the numbers assigned to individual GBIs in MDA budget documents. These numbers are the same as those used in the slide entitled “GBI Fleet Deployment History,” in Admiral Syring’s 2015 SMDC Conference presentation, as shown below (click on image for larger version). As Admiral Syring’s slide shows, the first twenty four deployed GBIs were CE-1s that were deployed before the end of September 2007. These GBIs were designated GBI 1 through GB 24. The slide makes clear that at that time only GBIs intended for deployment are included in this numbering scheme.

Deployment of GBIs resumed with the first CE-II GBI — GBI 25 – in October 2008. The first six CE-II GBIs – GBI 25 through GBI 30 – were deployed into empty silos, bringing the total number of deployed GBIs to the objective total of thirty. Admiral Syring’s slide shows three additional CE-II GBIs (GBI 31 to GBI 33) were deployed by the end of FY 2010. These three GBIs replaced existing deployed CE-I GBIs. Thus at the end of FY 2010, there would have been twenty one deployed CE-I GBIs and nine deployed CE-II GBIs.

In addition to the nine deployed CE-IIs, by the end of 2010 there appear to be two or three CE-II EKVs that were outside of this numbering scheme. These are the EKVs used in intercept test FTG-06, which took place in January 2010, and one or both of the EKVs intended for intercept test FTG-09, which was a salvo test (two interceptors against one target) scheduled for FY 2011. Following the failure of FTG-06, FTG-09 was cancelled in order to conduct FTG-06a, which also failed.

Following the failure of FTG-06a, deliveries of CE-II EKVs were suspended. MDA budget documents show that the first of the suspended deliveries was GBI 34. Thus at the time of this suspension, there would have been nine deployed CE-II GBIs (GBI 25 – GBI 33) and two CE-IIs expended in intercept tests. However, the GAO has stated that, at the time of the suspension, twelve CE-II GBIs had been delivered and ten of these had been deployed. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear (to me). One possible, although speculative, resolution to this discrepancy would be that the both of the interceptors for the planned FTG-09 salvo test were CE-II GBIs (as opposed to what is now planned as the first salvo test, FTG-11 in FY 2017, which will use one CE-I and one CE-II). Both of these CE-II GBIs would be outside the GBI numbering scheme, and the EKV not expended in FTG-06a could have been subsequently deployed, bringing the total number of deployed CE-II GBIs up to ten.

In 2013 and 2014, two CE-II EKVs were expended in the flight test CTV-01 and the intercept test FTG-06b. According to MDA budget documents, both of these CE-II EKVs were pulled from the ones that had already been deployed, bringing the number of deployed CE-IIs down to seven or eight.

Following the successful intercept test FTG-06b in 2014, MDA once again began accepting deliveries of CE-II-equipped GBIs. According to MDA budget documents, the next batch of eleven CE-II GBIs (GBI 34 to GBI 44) will be delivered before the end of FY 2016, bringing the total to eighteen or nineteen deployed. Taking into account the four deployed CE-II GBIs that in 2015 MDA Director Syring said would be withdrawn from deployment, the total number of deployed CE-II GBIs would then be fourteen of fifteen.

This counting scheme only totals twenty three CE-II EKVs. Given that the DoD Inspector General reports total of twenty four CE-IIs were delivered, and the conclusion above that sixteen CE-IIs will be deployed by 2017, it appears likely that there is one more CE-II GBI that is for some reason outside the GBI numbering system. (In addition, there is no reference to GBIs 45, 46 and 47 in the MDA budget documents.)

Production and delivery of GBIs will subsequently continue with eleven CE-II Block 1 GBIs (GBIs 48-58). This Block 1 numbering of GBIs appears to differ from the previous GBI numbering scheme in that it includes GBIs both for deployment and testing, and in particular it includes the GBI for the FTG-15 intercept test, scheduled for 2016. This would leave ten CE-II Block 1s for deployment by the end of 2017.

[1] Inspector General, U.S. Department of Defense, “Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle Quality Assurance and Reliability Assessment – Part A,” DODIG-2014-111, September 8, 2014, p. 7. Available at: http://www.dodig.mil/pubs/documents/DODIG-2014-111.pdf.

[2] For the CE-Is, these are FT-1 (2005), FTG-2 (2006), FTG-3a (2007), FTG-5 (2008), BVT-1 (2010), FTG-07 (2013), and FTG-11 (2017). For the CE-IIs, These are FTG-6 (2010), FTG-6a (2010), CTV-01 (2013), FTG-06b (2014), CTV-02+ (2015) and FTG-11 (2017).

[3] By budgetary materials, I primarily mean the annual MDA RDT&E Budget Justification Books available on the Department of Defense’s Comptroller’s website. For example, the FY 2016 materials are at: http://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2016/budget_justification/pdfs/03_RDT_and_E/MDA_RDTE_MasterJustificationBook_Missile_Defense_Agency_PB_2016_1.pdf.